Modern Symmetric Encryption 🔒

The beginnings of encryption

Classical Encryption

In 1500 BC a mesopotamian potter encrypted the method for making his pottery glaze and inscribed it on a clay tablet. This would have been important information and valuable to him as a tradesman, so the added effort for protecting the method for waterproofing and decorating his pottery would make sense. The ancient Hebrew people also made use of encryption utilizing a substitution cipher to encode the names of their enemies in parts of the bible as early as the 600s BC.

By the time the Roman empire overtook the Greeks in population and power, Julius Caesar improved the speed of encryption algorithms by taking each letter in a message and shifting it forward three places. Later, his nephew Augustas modified the cipher and instead shifted messages forward only one letter, three being apparently too hard for him.

By 1467, rather than encrypting one letter at a time, encryption schemes began using two letter blocks and keys based on words or phrases rather than a rotation number one through twenty-five like the Caesar Cipher. This brought an important feature to the enciphered messages, whereas previously any one plaintext-letter always translated to the same cipher-letter, with this new improvement, one plaintext encoded to many ciphertext possibilities for each letter, making decryption much harder.

The Dawn of Modern Encryption

World War II is considered by many to be the start of modern cryptography, with the advent of complex, easy to use machines rather than by-hand calculations. These cipher machines allowed for more complex ciphers to be executed faster and prevented calculations designed to break the encryption from being effectively done by hand. Various cipher designers from different countries contrived several machines for use in wartime and many continued the use of improved versions of those ciphers until the advent of modern computing systems which brought about the ability to greatly impact the effectiveness of those cipher machines.

At the same time the cipher machines’ security was being improved and their internal complications increased, mathematical advances in the field of cryptography likewise moved forward.

In the half century following World War II, increased research into cryptography from both private companies and public universities continued at an ever accelerating pace. Since it was critical for war, limits were imposed on the now much stronger, cryptography. These cryptographic systems were even restricted from export along with nuclear bombs and horses EAR. This is the landscape that bore the Data Encryption Standard or DES which is now considered woefully inadequate. It could have been better though, its original design had twice the key size but was curtailed by NSA’s “tweeks” to the algorithm prior to standardization.

The restrictions on cryptography were relaxed a bit in the 1990’s when the government realized it was a lost battle due largely to the efforts of international publishers and open source enthusiasts (however, the fact that encryption capabilities are pervasive has not stopped them from continuing to try restricting cryptography). In the mid-1990’s Triple DES was standardized publicly and another cipher called RC4 was leaked to the public. Nearing the 2000’s NIST announced that they would create an “Advanced Encryption Standard” better known as simply AES, and opened submissions up to the world.

Textbooks, cryptography classes, and online examples have created explanations of those three algorithms: 3DES, RC4, and AES. Depending on the level of the course, explanations of the ciphers can range from extremely simple like this:

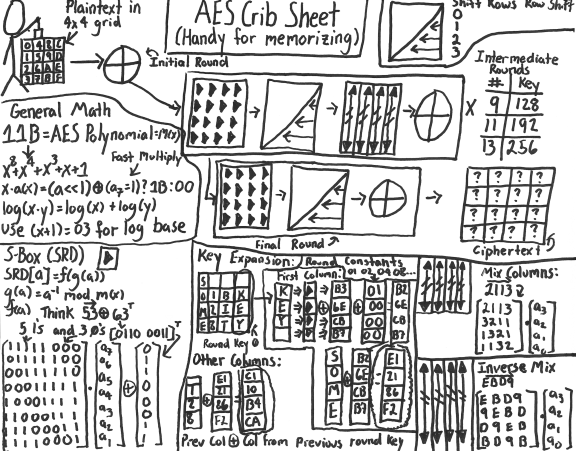

Or go into the full detail of the cipher down to following each individual byte like this:

Or even in a more fun format like this…

The problem is, when you do that you end up looking like you’re trying to explain a conspiracy theory.

However, each of those two different types of explanations are useful, depending on the level of understanding that you need. The problem comes when you try to extrapolate out of either, just that deep knowledge or, that very shallow knowledge with no additional context. Without that context, you end up with insecure systems. These systems could be nearly anything encrypting data: databases, applications storage, or transport mechanisms protecting data sent “over-the-air”.

Background

Before we get too far, there is some background information that will help with understanding some of the symmetric ciphers.

First, it is important to understand that there are two main types of symmetric key ciphers, block ciphers and stream ciphers. Both types have an output that is indistinguishable from random noise, as long as the algorithm is cryptographically secure. DES and AES are both examples of block ciphers by design and RC4 and Salsa20 are both stream ciphers. Block ciphers operate by chunking the data into “blocks” to operate over. Stream ciphers on the other hand, generate a “stream” of randomness to combine with a message. This combining is done using a logical XOR, which looks at a pair of bits (for example one from the pseudorandom stream and the other from the plaintext) and “sets” or marks down a “one” bit as the answer if the inputs are different, but does not “set” or marks a “zero” if the inputs are the same. The way that I was taught was “XOR is one or the other, but not both”.

One of the properties of XOR is that it is fully commutative. Imagine mixing the columns around in any order, no matter which side of the equal sign the columns land on, the equation is still true. Regardless of how you mix up the columns, the math behind the XOR equation holds true.

Stream Ciphers

The idea of using a random stream of data to encrypt data goes back to something described in 1882 by Frank Millar for securing the telegram. This idea was further developed in 1917 by Gilbert Vernam of Bell Labs in conjunction with Joseph Mauborgne from the US Army Signal Corps. The idea was to have a very long random stream, or one-time-pad, as a key and combine that with a message. Claude Shannon, a famous mathematician working at Bell labs mathematically proved that if the one time pad was truly random, then the cipher would be unbreakable. The goal of stream ciphers is to approximate that idea by generating a pseudorandom stream, something that looks random but was generated through a repeatable process, and combining it with a message to produce ciphertext. One of the best things about XOR is that commutative property, once you have the cipher text, if you can recreate the random stream (for example, by using a keyed stream cipher, or a potentially really long one-time-pad), you can XOR the ciphertext and the random stream together to get the plaintext message back.

Block Ciphers

Block cipher algorithms take in data and a key and output an array of random looking bits. But that information alone, without greater context is dangerous. Block ciphers have security properties that when using a secret key, a message goes in and random data comes out. However, if the message going into the block is the same every time then so is the output. That sounds like a good thing, but each block of output is only random if you only look at each block by itself. One excellent example of this effect was created by a student as an example for a class paper and added to the block cipher page of wikipedia. They encrypted a picture of Tux the Linux penguin and even though the data was encrypted, it was obvious by looking at the encrypted picture what the original image was.

This idea was greatly improved on by Filippo Valsorda in 2013 with a pop-art rendition of the ECB Penguin.

Understanding this effect from the beginning, cryptographers told people to never use this mode of block ciphers. Some cryptographic APIs, like Java’s however, “helpfully” made it the default.

Microsoft’s .NET API has a different default that is a little bit safer called CBC or Chaining Block Cipher mode, a concept developed in 1976. This mode prevents the “penguin problem” by taking the ciphertext output of the previous block and XORing it with the input to the next block.

CBC mode is further improved by adding in another input, one that gets passed along with the ciphertext, or is agreed upon before beginning any encryption. This input is called an “Initialization Vector”, commonly abbreviated as IV. Depending on the protocol this IV is combined somehow into the initial state of the cipher, so that encrypting the same message over and over with the same key, but with a different IV, can generate different output as well. Because the IV is an input to the encryption function at the start and is not related to the key or ciphertext, it is considered a public value and can be sent or stored alongside the ciphertext.

Cipher Attacks

CBC mode was used in protocols like TLS for many years because AES was fast, built into processors, and secure. But vulnerabilities arose in the way browsers implemented the CBC mode of encryption that allowed attackers to determine the private information encrypted on the browser’s side and allowed things like cookie theft and session hijacking. One such attack is called the BEAST attack from 2011 another is the Lucky 13 Attack from 2013.

The stream cipher RC4 was used as a way to mitigate both of these vulnerabilities at least until a patch came out with a workaround, in the case of BEAST; or a constant timed implementation, in the case of the Lucky 13 attack. RC4 however was not devoid of problems, there was a series of serious SSL security citations surrounding RC4 starting in 2013 and stopping finally in 2015 with the NO-MORE attack which again allowed attackers to reveal private data.

By themselves, modern encryption and decryption constructs are excellent at protecting data, they take data in and put random data out with no way to get back to the original without the key. But, because of that, there is no clear way to tell if the data being decrypted has been modified since it was encrypted.

A lot of these attacks involve the ability for an attacker to re-inject encrypted blocks or inject specific blocks into the data stream for the receiving end to decrypt. After the receiver decrypts the data it then does a check to make sure it is correct or valid. The timing of that check and the rejection or non-rejection of the decrypted data sent a signal to the attacker allowing them to glean information about the nature of the plaintext.

For this reason, modern encryption was modernized.

Modernized Modern Encryption

Authenticated Encryption

Authenticated Encryption was “designed to detect intentional, unauthorized modifications of the data, as well as accidental modifications”, in other words, protect against attacks modifying ciphertext.

Constructs

Encryption constructs using authenticated encryption began appearing in 2000 with research from IBM, universities, and RSA Laboratories. These constructs are specific ways to utilize an encryption cipher, like AES to create not only ciphertext, but also a “tag” that authenticates what was sent by the sender. There are several different ways to perform this authentication, and it is easy to think of it like a secure hash of the data. One way, used by the original design of SSL and TLS, is to put the authentication tag over the plaintext, then encrypt both the plaintext and the tag together. Another way is to do the opposite, encrypt the text, then create the authentication tag from the encrypted value. The final way is to combine those two ideas and encrypt both the plaintext as well as the authentication tag created from the plaintext. With any of these choices upon decryption, if the authentication tag does not validate, the decryption method returns an error, rather than plaintext; this is what is done in “modernly” modern cryptography.

Unlike basic encryption functions that just take in a key and plaintext and output ciphertext, or the slightly more advanced encryption modes that add an initialization vector, authenticated encryption instead takes in plaintext, a key, initialization vector, and something called “associated data”. This associated data is used to calculate the tag, and does not get encrypted. To understand the benefits of associated data, think about a postcard with a message protected using authenticated encryption. The message on the back of the postcard is encrypted and encodes the authenticated tag. Although the message is encrypted, the “to” and “from” addresses are in plaintext in order to assure delivery to the destination and to receive replies. In this case, the “to” and “from” are considered additional associated data. Without authenticated associated data, anyone can copy the message and the authentication tag any number of times and do things like reroute it or change the “from” address to make it look like it was sent by someone else. The recipient would know that the decrypted message was correct, but could think that it came from another source. Associated data as an input to encryption algorithm is used by Internet protocols like TLS 1.3 and QUIC to provide authenticated proof of the plaintext portions of the protocols.

With unauthenticated encryption, the decrypt function always outputs blocks or a stream of cipher text and it is up to the application to validate and reject “bad data”. With authenticated encryption however, there are two options for output, either the plaintext, or an error message saying that the input was bad. This error output will occur if any of the inputs change: the ciphertext, the tag, IV or the associated data. This ensures that the integrity of all the data is maintained.

Algorithm Examples and Usage

GCM

Currently, one of the most widely used authenticated algorithms is AES-GCM, this stands for Galois Counter Mode, which refers to both the way large amounts of data are encrypted (counter mode) and the way it is authenticated (Galois). The method creating the authentication tag, uses a Galois Field, a mathematically defined group of a very, very large set of numbers with defined ways of performing mathematical operations to ensure that all the resulting values for the operations fall into numbers in the set and making anything that would normally fall outside of the set of numbers wrap around to the start or end.

g(x) = x128 + x7 + x2 + x + 1

The “CM” or Counter Mode part of AES-GCM takes the AES block cipher and turns it into a stream cipher by repeatedly feeding a counter into the AES block cipher. This means that AES in GCM mode essentially creates a strung together series of blocks of bits that turns into a set of one-time-pads (each one AES-block long or 128 bits) that is then XOR’d with the data to be encrypted. Each of those ciphertext blocks created by XORing the plaintext and the AES function output are both saved off as a stream of cipher text, and at the same time fed into the multiplication function of the Galois Field. Each ciphertext block is multiplied by the previous one, wrapping around inside the Galois Field to create-small constant-size value. The final value is ultimately XOR’d with a value created by encrypting the IV with the private key; this provides the security for the tag because while anyone can multiply the ciphertext blocks together, only the key holder can do this final operation to create the tag.

When using a pseudorandom stream and XOR for encryption, one must not reuse, loop, or replay any part of the stream because it can lead to revealing the plaintext. In the same way, because GCM works by creating a pseudorandom pad, the same IV and key used together will always create the same pad. If that did not happen, you would not be able to decrypt the encrypted data given the same key. But, because of this, the randomness of the IV is just as important as randomness in the key and it is imperative that it is only used once. Otherwise, it is like reusing a one-time-pad and it destroys the security properties of the encryption scheme.

ChaCha20 + Poly1305

One of the other modernly-modern cipher systems in heavy use today is called ChaCha20+Poly1305. It is a descendant of the previously mentioned Salsa20 cipher. ChaCha20 is a stream cipher, and is used to create the pseudorandom string of bits by using a counter similar to the way that the GCM mode of AES works.

The authentication portion of the cipher, Poly1305 refers to the polynomial equation used to create the authentication tag. While 1305 comes from the special prime number, 2^130 - 5, which is used as the upper bound that the values when performing the math using the tag’s polynomial can hit before wrapping around. The “1305 prime” for the tag generator was chosen because it gives the ability to add in optimizations in the way that the message is broken up to perform the cryptographic operations. Additionally, much of the other designs in poly1305 lend themselves to a very fast implementation.

Algorithm Considerations

Algorithm speed is an important consideration, if adding in authentication to the encryption created a large overhead in calculation or size, no one would want to adopt it and its use would be relegated to obscurity. Which is why speed is such an important consideration for choosing an authenticated encryption algorithm. AES has been around since the year 2000, that means over the last 20 years cryptographers, programmers, and processor chip designers have been diligently working to ensure that the overhead of performing encryption with AES is not a significant detractor to its use. Chip designers have included special registers and specific instruction-sets in the microcode of their chips that allow for very fast performance of the different operations inside the AES algorithm. This makes AES faster than ChaCha20, at least on computers with that particular chip. Without special hardware however, ChaCha20 is superior; it was designed to be especially fast in software implementations without requiring special hardware tricks. Phones, tablets, and even some laptops are able to encrypt using ChaCha20 faster than they can encrypt with AES. Even still, there were instruction sets introduced on CPUs starting in 2018 that boost the speed of ChaCha20’s implementation over the hardware-improved AES in certain circumstances. One issue is that it uses twice as much power, generates extra heat, therefore causing the CPU speed to throttle down, and in the long run make everything slower. Additionally, ChaCha20 was also designed to defeat problematic side channels that plague AES implementations. Because of the way that AES was designed, implementations have added optimizations that can lead to issues. When these timing issues happen, if an attacker is looking closely at how long operations were taking it could lead to them being able to divine the key. Because all of ChaCha20’s operations happen in constant time, there is not an opportunity for any timing attacks.

Device Encryption

Data stored in our mobile and desktop devices also need encryption to protect data at rest and with modern operating systems that is now more of the norm whereas even a few years ago it was more of a rarity reserved for high security systems or large enterprises.

Mobile

Mobile OS’s require fast access to data, because of that added authentication steps sometimes do not authenticate the data, others use a bit of a lighter-weight authentication mechanism.

iOS

In Apple’s iOS systems, secret data protected on a hardware chip combines with things like pins or passwords to create AES keys used to protect system data. iOS uses AES in a mode called XTS which is pretty complicated and gets into how disk drives work in order to adequately explain. The biggest take away is that it is not an authenticated cipher. However, on the tightly controlled Apple hardware, there are not many easy ways to get to the deep sector level of the drive to attempt modification of the data. This is why iOS apps still should encrypt any important data to secure with some type of authenticated scheme.

Android

In Google’s Android system, device-level encryption uses similar hardware chip components to protect encryption keys as well as AES for data encryption. Android uses the Chaining Block Cipher (CBC) mode of AES and creates the Initialization Vectors (IV) by taking a hash of the encryption key and combining it with the data’s location on the disk.

Desktop

There’s less and less of a gap between desktops, laptops, and mobile devices these days, with companies like Apple using a lot of the same low-level code for their mobile OS and desktop OS, or Microsoft using the same version for both tablets and desktops.

Apple

On Apple desktops and laptops, the process used is essentially the same as iOS due to the closeness of the underlying operating system codebase.

Windows

On Windows, disk encryption can happen two different ways. By default, in the regular consumer version of Windows 10 a key is generated for protecting files, and uploaded to Microsoft for safekeeping, that way if you lose your password you can just recover access to your data through a text message. Users or system administrators can go into the settings and configure a program called Bitlocker which will allow local key recovery using a flash drive or a printout of a long recovery key. Both of these options now use AES-XTS like Apple.

Cloud Crypto

Besides Transport Layer Encryption, there are two different use cases for encryption in the cloud, first: data at rest, and secondly: encrypting application data. To differentiate between these two types of encryption, consider data-at-rest anything that is done automatically by the cloud service itself for all of one specific type, or even all of the data, that is stored by the cloud provider. Application data encryption is where the cloud provider provides a specific interface for applications running on the cloud services to utilize keys to encrypt data within their application.

Data-at-Rest

AWS

AWS allows administrators to set up encryption for their stored data using AES-GCM providing a nice authenticated option for them to use to protect their data.

GCP

GCP uses the same, by implementing AES-GCM to protect the data at rest in their environment. Some added bonus information here: whenever Google sends data across their networks they automatically wrap the data in a special protocol called ALTS that allows them to transfer data using either AES-GCM or something called AES-VCM, which uses a special authentication method based on integer arithmetic designed to be especially fast on 64-bit processors.

Azure

Microsoft Azure’s data-at-rest storage disappointingly only uses the CBC mode for encryption citing ease of storage retrieval as the reason.

Application Data

On the application data encryption side, each cloud provider has an API that application teams can use to encrypt specific pieces of data from their code.

AWS

With AWS, application data, similar to their data-at-rest, can be encrypted using AES-GCM, the interface allows for providing additional associated data (the extra, non-encrypted data we talked about before) as well as an initialization vector, which the developer is left to make sure is never reused and always completely random.

GCP

In Google’s cloud, applications are given the ability to do something called “Envelope Encryption” this encryption API allows developers to simply encrypt data by only passing a byte array and key name. Under the covers, this uses a key management scheme designed by Google that uses a key encrypting key to protect the key that encrypts the data. This data encryption key and the IV are randomly generated on the fly each time new data is written.

Azure

Azure, on the other hand does not provide an API for symmetric encryption of data at all, however, the API allows applications to create their own, securly stored, keys and use them inside the application to encrypt data using any encryption method supported by the programming language in use. Of course the examples in their documentation use CBC mode.

Does it help protect you?

The problem with encrypting data in the cloud is that most people do not understand the threat model that it protects against. Cloud encryption does not protect against the cloud provider seeing the plaintext data; they have to be able to decrypt the data so that they can sort it, index it, and provide it to the end user of the data. It also does not protect against operators setting permissions incorrectly on the data where anyone could get access to it through the regular web-interface or application. This is what happened to Capital One about a year ago. 140,000 social security numbers and 80,000 bank account numbers were accessed by the malfeasant, even though they were encrypted. Because the access rights set on the data interface allowed anyone hitting the cloud service to tell the provider to go get the keys and decrypt the data before sending it out of the cloud.

Then what does cloud encryption protect against? It prevents someone with physical access to the harddrives from gaining access to the raw data. One could achieve this physical access either through breaking in and yanking drives, finding un-erased drives in the trash (however unlikely that would be), or by being an insider working in the datacenter with access to the physical devices.

Another way to use the cloud keying mechanisms to protect your data depends on the particular way that the crypto-systems in the cloud are set up, cloud administrators can do something called “byok” or bring-your-own-key, this allows the admin to provide a key to the cloud from their local site. You would want to do this if you were worried about the key persisting in the cloud after you did not want it to, and trusted the cloud provider to delete copies of the key when asked. Cloud consultants pitch this as a way to quickly remove the cloud provider’s access to a given key or set of keys, rendering the data unreadable. You’d want to do this after terminating a cloud agreement to make sure they could not get to the data anymore, or to quickly destroy the ability to decrypt the data. A similar concept called key caching is one step removed from that, it is where every few minutes or hours the cloud provider makes a call back to the local company’s key server to request a key in order to perform cryptographic operations on data. In an example not too far outside the realm of plausibility… given their access to the keys, a cloud provider could turn over data without your intervention when faced with a court subpoena. However, if you knew that the request for data was imminent and wanted to retain the ability to fight that subpoena to prevent the court from gaining access to it, you could revoke the cloud provider’s access to the keys and with it prevent their ability to provide meaningful data.

Another example where companies can use Cloud Encryption to help protect data is in using more complex data access configurations where you allow specific groups access to the stored encrypted data where they could see things like location of the data and possibly plaintext information about what it is associated to, but give other groups access to the data as well as the ability to tell the cloud service to decrypt the data. An example of this would be a select group of people, like doctors, that can see images containing sensitive information such as dental scans, and other users, like office staff, that have access to see information about people that have had dental scans, but do not have a need to see the actual images. As long as the access rights to the encryption keys are managed correctly, the data will remain secure and protected.

Encryption Future

Everything we’ve talked about so far has been in place for the last 5 or so years, but of course there are some not using these best practices.. Others are already working on finding the next best thing for encryption and bringing it into the modern libraries and incorporating it into systems utilizing cryptography.

Nonce Misuse Resistance

One of the things you may have noticed is that AES-GCM is extremely popular. It is used all over, in browsers, clouds, and in applications protecting important data for all types of uses for all types of people. One problem with AES-GCM is not everyone always gets it right, very similar to the way people can see “AES” and start using it in ECB mode, GCM allows implementers to easily accidentally shoot themselves in the foot. If the same initialization vector is used with the same key on different data, you can end up in a situation where the data can be decrypted... without knowing the key. Newer encryption constructs that have not made it into the mainstream product lines quite yet have been designed to help protect against this “foot-gun” by changing the algorithm to where using the same IV with the same key multiple times does not affect the security properties of the encryption system as a whole. One of these modes is called AES-SIV, in SIV mode, rather than taking an IV as input into the algorithm, all of the data is hashed first, then the resultant hash is fed into AES as an initialization vector. Like GCM, a counter is incremented for each new AES block that is delivered to create the pseudorandom stream that will be XOR’d with the plaintext.

CAESAR

The CAESAR competition began in 2014 and wrapped up last year was designed to find a replacement for AES-GCM that was robust and suitable for mass adoption.

Lightweight cryptography

One thing that is ongoing is a process designed to help with processors in smaller devices in constrained environments is to look at the algorithms used and change the insides to make sure they take as little time and as few resources as possible. This search is ongoing but expected to complete over the next few years.

Homomorphic encryption

Homomorphic encryption gives the ability to perform tasks and calculations over encrypted data, but technically it is not new. HE has been around since the 1970’s, but has not seen much use until recently. And with good reason, because there is one problem with homomorphic encryption, it is very processing intensive and can end up taking quite a long time to complete any operation. There are several research institutions and companies that have products and tools with support for HE, IBM recently released one that works on MacOS and iOS, with support for Linux and Android coming soon.

Reaction to Quantum Computing

Last, but not least, there is a threat to different types of encryption mechanisms including symmetric encryption. However, this bit is easy, just double the encryption security level, in other words, take the minimum key size from 128 to 256 and decryption is safe from the threat of quantum computers.